“An unfolding reality of orbit wars, invisible domes, and a world racing against time.”

- The U.S. Vision: The Global Missile Shield Dream

- Global Reactions: How Rivals and Partners View the Shield

- Why Boost-Phase Interception is Key

- India’s Quiet Ascent: Building a Missile Shield

- Countering the Chinese Arc: BMD + Early Warning

- Project KUSHA: India’s Indigenous Air Defence Game-Changer

- The New Global Doctrine: Dilemmas of the Missile Shield Era

- Conclusion: Not Just a Shield, But a Signal of a New Era

A World in Flux: The Warfighting Clock Now Ticks in Milliseconds

Every second, the world rewires itself. Not just in newsrooms or data centers, but in battle doctrines and satellite grids. From hypersonic glide vehicles blazing at Mach 20 to AI-enabled target acquisition, we’re witnessing the transformation of war. In this volatile landscape, defense is no longer about outgunning the adversary — it’s about out-calculating them. This profound shift is driving the race to develop a global missile shield

In this volatile landscape, defence is no longer about outgunning the adversary — it’s about out-calculating them before a launch ever leaves the silo. Missile shields, once science fiction, are now the most sought-after military umbrellas on the planet.

Leading this push is the United States, with its ambitious “Golden Dome” a conceptual shield that aims to intercept everything from rogue missile launches to peer-state salvos. But as America builds its “impenetrable sky,” China and Russia are watching, intensifying their own offensive and defensive innovations. So is India, adapting its strategy to a rapidly shifting global chessboard.

And thus begins a silent arms race — not on Earth, but in orbit. This global pivot towards defensive capabilities signals a profound shift, with far-reaching implications for international stability and the future of conflict.

The U.S. Vision: The Global Missile Shield Dream

The U.S. has long pursued missile defence — from Reagan’s 1983 “Star Wars” (Strategic Defence Initiative) to today’s advanced THAAD and Ground-Based Interceptors (GMD). But the “Golden Dome” is a leap beyond existing capabilities. It’s not a single project but a comprehensive vision to create a combat-proven, AI-integrated, space-based system capable of detecting and destroying incoming threats mid-flight. The Golden Dome represents the U.S. vision for a comprehensive global missile shield.

According to media concept sheets from entities like Lockheed Martin, the Golden Dome envisions a layered defence system protecting the entire continental U.S. from:

- Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs)

- Hypersonic Glide Vehicles (HGVs)

- Low-orbit satellite attacks

- Drone swarms and maneuvering re-entry vehicles

The system would integrate:

- Space-based sensors and interceptors for early launch detection (crucial for boost-phase interception).

- Ground-based midcourse defence (GMD) sites for ICBM tracking in space.

- Next-gen kinetic interceptors, potentially laser-aided or railgun-based in the future.

- Advanced fire-control architecture like C2BMC (Command and Control Battle Management and Communications) to avoid saturation and integrate data from various systems (e.g., Navy’s Aegis, Air Force’s SBIRS satellites, Army’s PAC-3 interceptors).

It’s designed to be more than just a missile shield; it’s envisioned as a digital dome of deterrence. With an approximate $12 billion annual budget for the Missile Defence Agency and initial project costs estimated between $161 billion and $542 billion over 20 years, this staggering investment highlights a profound commitment. This effort demands a “Manhattan Project-scale” urgency, blending defence and commercial innovation for rapid deployment.

The Golden Dome is implicitly aimed at countering a future where China and Russia field advanced first-strike options, seeking to enhance U.S. and allied freedom of action and reduce the perceived value of an attack.

Global Reactions: How Rivals and Partners View the Shield

Far from being a purely defensive measure, the U.S. missile shield is widely perceived by China and Russia as a strategic provocation, seen as an attempt to neutralize their nuclear deterrence and undermine the principle of mutually assured destruction (MAD). This fuels a dangerous “stability-instability paradox”: while defence might reduce the risk of nuclear conflict, they could paradoxically make limited conventional conflicts more probable, as nations might feel less constrained by nuclear escalation.

Russia and China’s Stance:

On May 8, 2025, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin and Chinese leader Xi Jinping issued a statement strongly condemning the U.S. “Golden Dome” project. Russia and China view the U.S.’s pursuit of a global missile shield as a threat to strategic stability.They rejected its “left-of-launch” capabilities and the orbital deployment of interception systems, calling it a threat to the balance between offensive and defensive arms.Russia and China view the U.S.’s pursuit of a global missile shield as a threat to strategic stability.

- Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova stated that the project “undermines the foundations of strategic stability as it involves the creation of a global missile defence system,” adding that it “revives Cold War-era tactics and could destabilize long-standing arms control frameworks.”

- While Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Sergeyevich Peskov later softened the tone, calling the plan a “sovereign matter,” he emphasized the urgent need to rebuild the arms control architecture for global security, stating that “the very course of events requires the resumption of contacts on issues of strategic stability.”

Russia’s Perspective:

- Moscow has consistently called the U.S. BMD a “first-strike enabler,” suggesting it could embolden the U.S. to launch preemptive attacks.

- Russia has rapidly developed systems to bypass BMDs, like the Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle and the Kinzhal air-launched hypersonic missile.

- The assessment suggests Russia’s boosted hypersonic weapon count is expected to increase from 200-300 to 1,000 weapons in 10 years. These “boosted hypersonic weapons” often refer to aero-ballistic missiles, which are launched from air platforms and are unpowered after boost, using aerodynamic guidance.

- They’ve also announced nuclear-powered cruise missiles like Burevestnik, designed for unlimited range and radar evasion. Moscow has warned that if the U.S. proceeds with a full-scale space shield, Russia will expand both its orbital defence and offense capabilities in response.

China’s Response:

- Beijing views U.S. missile defence as “a strategic imbalance that triggers arms races.”

- China has significantly accelerated its own advanced missile capabilities, including the DF-17 hypersonic missile and fractional orbital bombardment systems (FOBS).

- And just now we all saw the new DF-61 ICBM missile in the China Victory Day parade, Who was giving a different message to the world in the parade.

- China’s possession of boosted hypersonic weapons is currently at an estimated 600 and is projected to increase to 4,000 weapons in 2035.

- In October 2021, China tested a hypersonic glide vehicle that orbited Earth before striking its target, alarming the Pentagon.

- China’s strategic doctrine increasingly includes space warfare, with satellite kill vehicles, jamming, and directed-energy weapons.

- Both nations heavily invest in MIRV (Multiple Independently-targetable Re-entry Vehicles) with advanced decoys, aiming to overwhelm defences with saturation attacks. This global ripple effect sees other nations, including those in the Middle East and Europe, also seeking advanced defence capabilities, intensifying regional arms races. For instance, Europe is experiencing a “missile renaissance” in response to regional threats, re-evaluating long-range conventional missile capabilities.

Why Boost-Phase Interception is Key

To grasp the Golden Dome’s revolutionary potential, we must analyze a missile’s flight phases:

- Boost Phase: This short phase, from launch to space, sees the missile’s engine burning fiercely. This is its most vulnerable moment due to its predictable path and intense heat signature. However, ground-based radars like the S-400 have minimal time to track it before it exits the atmosphere, making boost-phase interception by current ground systems extremely challenging.

- Midcourse Phase: The longest and trickiest phase, where the missile travels through space. It can deploy decoys (even simple nuts and bolts) or multiple warheads, and some can change direction, making real-vs-decoy discrimination difficult.

- Terminal Phase: Warheads re-enter the atmosphere, racing towards targets. There are only seconds to react, making effective interception exceptionally difficult for conventional systems.

For current ground-based systems, their “eyes” are limited. India’s S-400, for example, while theoretically capable of intercepting threats up to 400 km, applies mainly to predictable ballistic arcs. Its radar refresh rates are too slow to reliably lock onto a Mach 10 maneuvering hypersonic missile, and its missile types are optimized for ballistic or cruise targets, with kill probability dropping drastically against hypersonic. This means, despite advanced systems, a hypersonic nuclear missile launched today would, in all likelihood, hit its target.

This is precisely the vulnerability the Golden Dome aims to eliminate. Its space-based satellite kill layer can detect ballistic and hypersonic missiles immediately upon launch and destroy them in their most vulnerable boost phase, preventing them from ever becoming unpredictable Mach 20 threats. This requires global interceptor coverage, which means deploying weapons in space – likely a constellation of 1,300 to 2,000 interceptor satellites in low Earth orbit or potentially space-based lasers capable of focusing high-energy beams to disable targets at light speed.

India’s Quiet Ascent: Building a Missile Shield

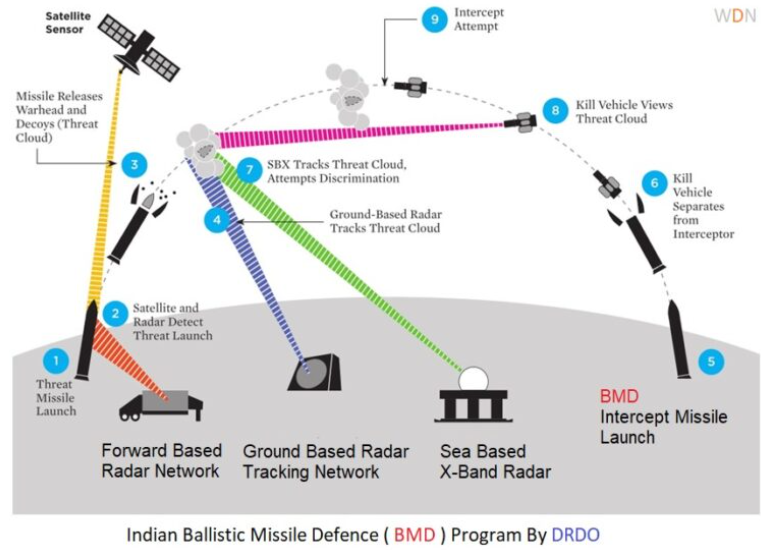

While the U.S. pursues a highly visible “dome,” India is charting a different, quieter course—constructing a multi-layered missile shield with strategic silence. like While the U.S. builds a highly visible dome, India is quietly developing its own components for a regional missile shield.As China continues to field advanced systems like the DF-17 hypersonic and Pakistan enhances its tactical nuclear capabilities with missiles like Nasr, India’s Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) programme together with Mission SUDARSHAN CHAKRA and Project KUSHA (ERADS) , AKASHTEER been maturing steadily.

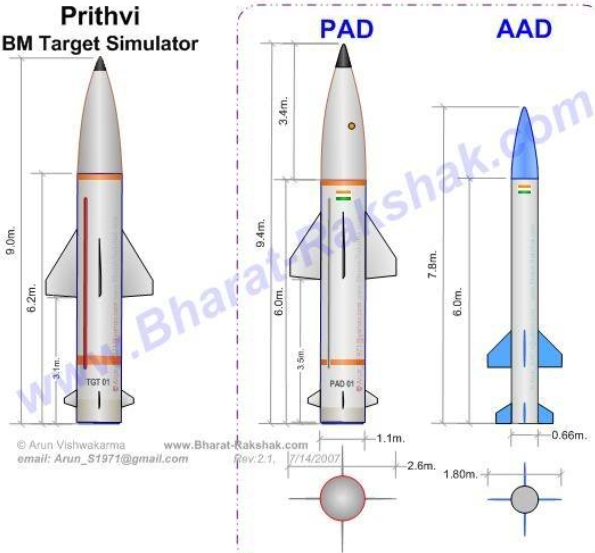

Developed by the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO), India’s dual-layer system (comprising PDV and AD interceptors) is undergoing its final trials, with new satellite-based sensors quietly integrated into its early warning network. The Prithvi Defence Vehicle (PDV) intercepts threats outside the atmosphere (exo-atmospheric), while the Advanced Air Defence (AAD) system targets incoming missiles within the atmosphere (endo-atmospheric). There are also reports of a potential third layer, possibly akin to Israel’s Iron Dome, to provide short-range defence for critical urban centers like Delhi and Mumbai.

India’s approach isn’t about mimicking the U.S. model but adapting the strategic logic to its unique geopolitical environment. Where the “Golden Dome” is publicly marketed for deterrence and funding, India’s BMD program is characterized by stealth and strategic ambiguity. Yet, the core intent remains the same: neutralize potential nuclear blackmail and protect strategic assets.

India’s indigenous BMD program is structured in two key phases:

- Phase-I: Primarily designed to counter missiles with a range of up to 2,000 km, focusing on threats from Pakistan. This phase includes PAD (Prithvi Air Defence) and AAD (Advanced Air Defence) interceptors.

- Phase-II: Developed to counter longer-range and intercontinental threats, particularly from China. This phase features more powerful interceptors like AD-1 and AD-2, with active radar homing. In April 2023, DRDO successfully tested the AD-1 interceptor against long-range ballistic missile targets, demonstrating THAAD-class capabilities for high-altitude interception.

India isn’t just building a missile shield; it is showcasing its strategic power on the world stage. This investment is not an economic burden, but a forward-looking step.

As one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, India is fully capable of meeting its defence needs. This is a visionary investment to solidify its sovereignty and global standing. India is not a rising power, but an established global superpower, ensuring its security and progress simultaneously.

Countering the Chinese Arc: BMD + Early Warning

The People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) of China poses a significant strategic challenge, with advanced missiles like the DF-21D (“carrier killer”) and DF-26 (intermediate-range ballistic missile). Coupled with increasing Chinese naval presence in the Indian Ocean, India faces complex, multi-vector threats.

In response, India is integrating a range of systems:

- S-400 Triumf air defense systems from Russia, already deployed strategically.

- The “Triumf” is the project name given to it by Russia, which translates to “Triumph” in English, signifying a decisive victory or success.

- Long-Range Tracking Radars (LRTR) for crucial early launch detection.

- Discussions are reportedly underway with Russia for the implementation of the ultra-long range Voronezh radar system in India. This highly advanced early-warning radar would significantly enhance India’s ability to detect ballistic and hypersonic missile launches from thousands of kilometers away, providing an unprecedented level of strategic foresight and elevating India’s position in global missile defence architecture.

- A proposed Indian Missile Tracking Ship (INS Dhruv), with state-of-the-art ocean-based surveillance.

- Advance-integrated Command-and-Control (C2) systems for faster and more accurate decision-making.

India’s BMD isn’t a copy; it’s a pragmatic adaptation to its specific theater of operations. When America builds a sky-shield, China responds with faster weapons. And those Chinese weapons don’t just threaten America they bring India within range. Thus, India needs to pre-empt its adversaries’ hypersonic edge, consider U.S.-style space surveillance networks, and continue investment in hypersonic interceptors. In a world where adversaries develop sophisticated offensive capabilities and their own shields, India understands it cannot remain exposed.

Project KUSHA: India’s Indigenous Air Defence Game-Changer

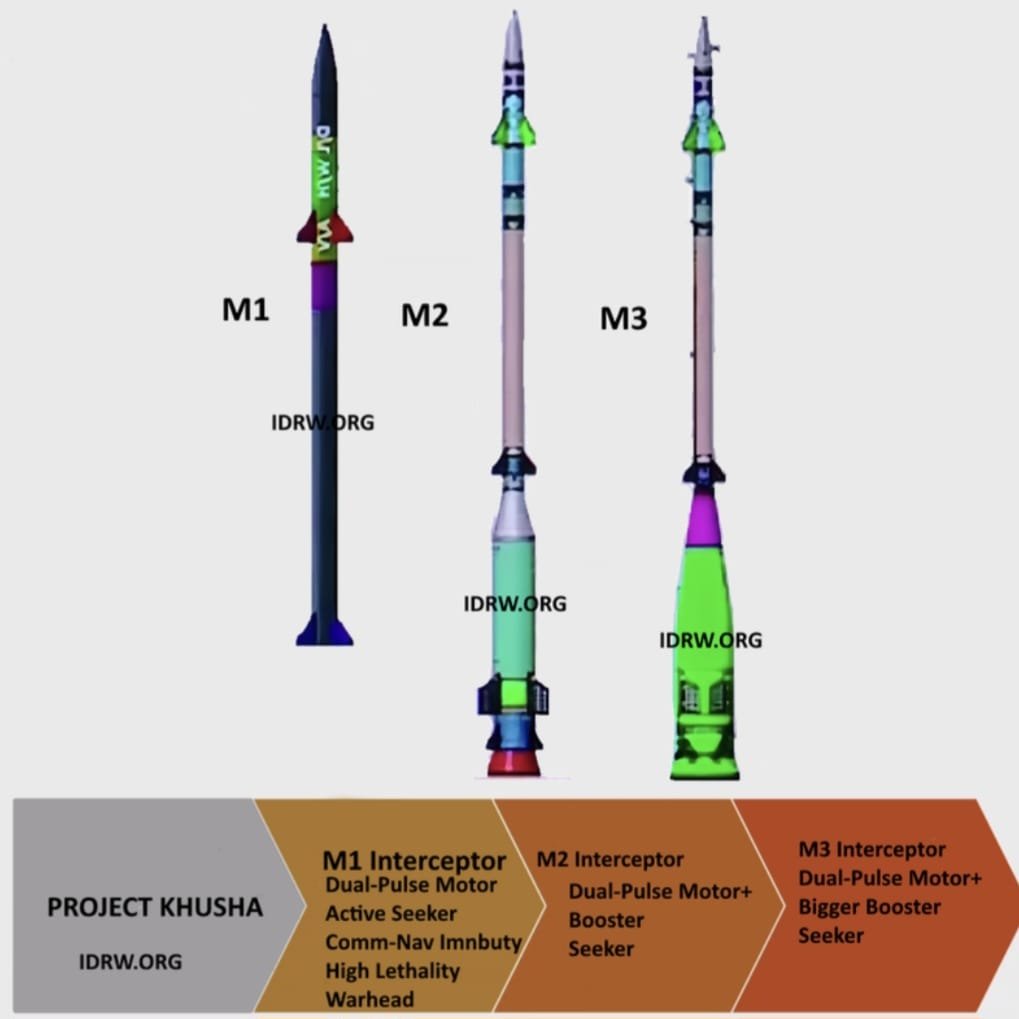

Beyond its dedicated Ballistic Missile Defence, India is making a significant leap in indigenous air defence with Project KUSHA, also known as the Extended Range Air Defence System (ERADS). Approved by the Cabinet Committee on Security in May 2022, and with Acceptance of Necessity granted in September 2023 for five Indian Air Force squadrons at an estimated

cost of ₹21,700 crore (approximately US$2.6 billion), Project KUSHA is envisioned as a multi-layered, mobile surface-to-air missile system.

Project KUSHA is designed to fill the critical operational gap between the 80 km range Medium Range Surface-to-Air Missile (MR-SAM) and the 400 km range S-400 Triumf system, ultimately aiming for capabilities comparable to Russia’s advanced S-500. It’s a cornerstone of India’s ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ (self-reliant India) initiative in defence.

Key aspects of Project KUSHA include:

- Three Interceptor Variants: It will feature three types of interceptor missiles, M1 (150 km range), M2 (250 km range), and M3 (350 km range), sharing a common kill vehicle but with different boosters for varied ranges. These are designed to neutralize a wide spectrum of aerial threats, including stealth fighter jets, cruise missiles, drones, and even Mach 7 anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs).

- Advanced Radars: The system will incorporate an indigenously developed Long-Range Battle Management Radar (LRBMR) with Digital Beam Forming (DBF) and Gallium Nitride (GaN)-based Transmit/Receive modules, offering a detection range exceeding 500 kilometers. This radar is expected to have a smaller physical footprint than foreign systems, enhancing mobility.

- High Kill Probability: Project KUSHA aims for a single-shot kill probability of over 80%, increasing to 90% or more in salvo launch mode.

- Integration: It will seamlessly integrate with the Indian Air Force’s (IAF) Integrated Air Command and Control System (IACCS), creating a robust and automated air defence network.

- Development Timeline: The first trial for the M1 missile is expected in September 2025, with M2 and M3 trials in 2026 and 2027 respectively. Phased induction into the Indian Air Force and Indian Navy is expected between 2028 and 2030.

Project KUSHA represents India’s ambitious stride towards achieving strategic autonomy in air defence, reducing reliance on foreign imports, and equipping itself to counter the most advanced aerial threats of the future

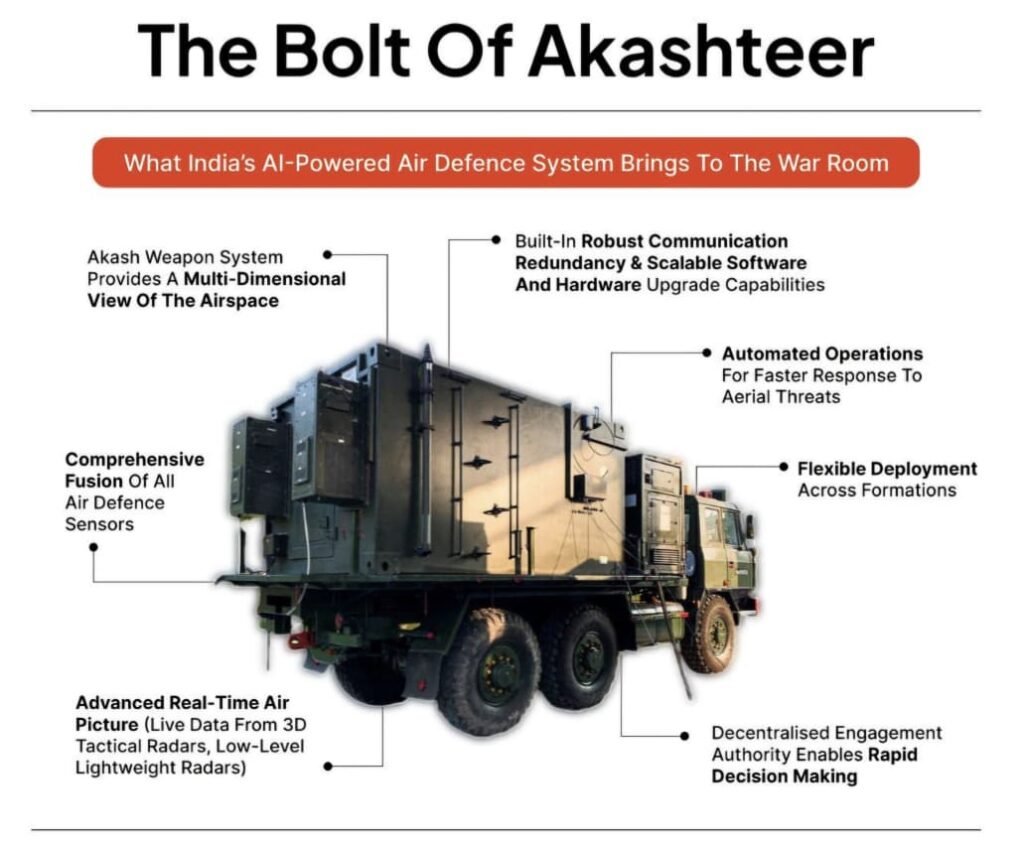

The AKASHTEER system is a significant advancement in India’s air defence capabilities.

1. AI-enabled, Automated Air Defence System:

- AKASHTEER is an AI-enabled, fully automated Air Defence Control and Reporting System (ADCRS).

- It is designed to automate the detection, tracking, and engagement of enemy aerial threats, including aircraft, drones, and missiles.

2. Indigenous Development:

- Developed by Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL) in collaboration with the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

- It is a core part of India’s “Atmanirbhar Bharat” (self-reliance) initiative in the defence sector.

3. Key Capabilities and Features:

- Multi-Sensor Fusion: The system integrates data from various sources, including different types of radars (3D Tactical Control Radars, Low-Level Lightweight Radars), and sensors. It also incorporates information from ISRO’s Earth observation satellites and the NAVIC navigation system. This fusion provides a comprehensive, real-time air picture to all involved parties.

- Real-Time Command and Control: It is designed to provide tactical command and control, enabling faster and more efficient decision-making. Unlike traditional systems that rely on manual input and a chain of command, AKASHTEER can make automated, real-time engagement decisions.

- Decentralized Engagement Authority: The system empowers frontline commanders with the authority to engage threats without waiting for central clearance, which is critical for rapid response in high-conflict zones.

- Mobility and Versatility: AKASHTEER is a vehicle-based system, making it mobile and suitable for deployment in various terrains and operational scenarios, from border defence to active war zones.

- Seamless Integration: It connects with other systems used by the Indian Armed Forces, such as the Indian Air Force’s Integrated Air Command and Control System (IACCS) and the Indian Navy’s TRIGUN system, to ensure synergy and prevent friendly fire.

4. Strategic Importance:

- AKASHTEER is a major step towards modernizing India’s air defence network and strengthens the Indian Army’s Corps of Army Air Defence (AAD).

- By providing a layered and cohesive defence, it aims to protect India’s airspace from a wide range of threats, including modern drones and missiles.

- The system’s indigenous nature and use of cutting-edge technology, including AI, position India as a leader in automated air defence capabilities.

The New Global Doctrine: Dilemmas of the Missile Shield Era

The proliferation and advancement of BMD systems signal a profound shift in strategic thinking. The traditional Cold War doctrine of “mutual assured destruction” (MAD), where retaliation prevented first strikes, is giving way to “deterrence by denial.” Nations now aim to absorb and neutralize incoming strikes, reducing the value of initiating an attack.

However, this shift carries significant risks, potentially fueling a new arms race dynamic:

- Adversaries may build more missiles to overwhelm shields.

- They might develop systems to bypass interception, like stealthier re-entry vehicles or more sophisticated hypersonic.

- This technological arms race increases the economic burden on all nations, potentially diverting resources from other crucial development areas.

In this relentless game of shield and spear, deterrence is dynamic, technologically driven, and demands constant adaptation. This evolution also surfaces critical ethical and strategic dilemmas for the global community:

Autonomous Warfare Systems: The prospect of fully autonomous warfare systems, where space-deployed units make real-time combat decisions without human intervention, raises profound questions about accountability, moral responsibility, and the principle of meaningful human control over lethal force. If such a system misclassifies and fires, who is responsible? What are the risks of algorithmic bias or unintended escalation? International debates are ongoing regarding the need for robust ethical guidelines and legal frameworks to prevent an unregulated arms race in these technologies.

Militarization of Space and the Outer Space Treaty: The pursuit of “dominance” through space-based defence has ignited a silent arms race in orbit. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, signed by the United States, the Soviet Union, and China, aimed to use outer space “exclusively for peaceful purposes.” It strictly prohibited the placement of nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction in orbit, on celestial bodies, or in outer space in general.

- Article IV specifically states: “States Parties to the Treaty undertake not to place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying nuclear weapons or any other kinds of weapons of mass destruction, install such weapons on celestial bodies, or station such weapons in outer space in any other manner.”

- However, as interpreted by bodies like the UN Office for Outer Space Affairs, a critical loophole exists: as long as a nation is not placing weapons of mass destruction (defined as atomic explosive, radioactive material, lethal chemical, and biological weapons) in space, its space weapons (e.g., conventional kinetic interceptors, lasers) are not considered illegal under the treaty. This geopolitical impact outweighs the legal technicality, as countries now design satellites for offensive operations, blurring the lines between peaceful and military uses of space and further eroding arms control treaties.

- Countervalue Threats and Prioritization: Protecting “countervalue threats” (attacks aimed at civilian, economic, or cultural targets) implies governments must prioritize which cities or assets receive extra protection. This raises difficult ethical questions about population thresholds and national values.

In this escalating environment, India finds itself in a unique position. Despite demonstrating ASAT (anti-satellite) capability through Mission Shakti in 2019, India has consciously distanced itself from space militarization. However, with the Golden Dome’s deployment, India will face a crucial decision: become a tech-sharing partner with the U.S. within a regional missile tracking and command system, or develop its own orbital surveillance and space defence architecture? While DRDO is developing high-energy laser systems, their urgent deployment will increase. If China deploys its own version in response, India will inevitably need to establish counter-capabilities for a regional buffer zone, despite the immense economic and technological challenges.

Conclusion: Not Just a Shield, But a Signal of a New Era

India’s growing Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) system, complemented by ambitious indigenous projects like KUSHA and the pursuit of advanced early warning systems like the Voronezh radar, collectively send a clear signal to both Beijing and Islamabad: they won’t even dare to lift their eyes in our direction, let alone think of touching our nation. So India’s pragmatic model adds a new layer to the emerging global missile shield.

While the U.S. “Golden Dome” represents an ambitious dream of near-absolute immunity and space dominance, India’s model is more pragmatic and regionally focused: to defend key assets, deter regional aggression, and prevent escalation across the full spectrum of aerial threats. This comprehensive shift towards denial over retaliation defines a new global defence paradigm. As missiles become faster, stealthier, and smarter, a robust and layered air and missile shield is no longer a luxury. It has become a strategic necessity for national survival. This arms race pushes technology’s boundaries, from laser-based weapons to advanced quantum communication, and accelerates the militarization of space.

The missile and air defence era is not a finish line. it’s the beginning of a new kind of arms race where defence is no longer a fallback, but the front line. And unless diplomacy catches up with technology, the next war might not start on Earth at all.

Verified References:

- U.S. Missile Defence Agency

- U.S. Department of Defence Annual Report to Congress on China’s Military Power (Latest available year)

- Russian Ministry of Defence official briefings (as reported by reputable international news agencies)

- DRDO Annual Report (Latest available year)

- “India Successfully Tests AD-1 Interceptor” – The Hindu, April 2023

- Congressional Research Service (CRS): Missile Defense Systems Overview (Latest available year)

- SIPRI (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute) Arms Control Database & Yearbooks

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS) – The Military Balance (Latest Edition)

- Outer Space Treaty of 1967 (Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies)

- United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) publications on space law.